The Minoans: The Oldest Civilisation In Europe

Despite both Greek and Roman societies being more well-known, the Minoans easily predate them both. The Minoans are, in fact, the most ancient civilisation in Europe. Nowadays, it’s all about the Greeks and the Romans, but, in my opinion, these guys deserve a revisit.

Minoan civilisation was predominantly based on the island of Crete, the largest and most southerly of the Greek islands.

The islanders never actually referred to themselves as the “Minoans.” They got their name courtesy of the 19th century archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, who, when he began excavating at Knossos in 1900, thought he had discovered the palace of the legendary King Minos.

According to the myths, King Minos was a son of Zeus; he owned a labyrinth (designed by Daedalus, father of Icarus) where he kept a minotaur. Minos fed the minotaur fourteen humans every nine years.

Minoan culture flourished from 2600 to 1400 BC when they disappeared without a trace. Well, “without a trace” does them a bit of a disservice, they have, in fact, left us quite an unbelievable amount of pottery, art and ancient buildings to peruse. Much more than a “trace.” Throughout this article are images of some of the beauties they left behind.

It was the Minoan’s relatively swift downfall that all but erased them from European history (more on that later). But, at the time, they were hugely influential in the region.

There is evidence that the first human (or perhaps pre-human hominid) reached Crete some 130,000 years ago; however, it was not until 5000 BC that the first signs of agriculture are found.

A number of Minoan palaces have been unearthed on Crete and other nearby Aegean islands, but the largest and most impressive is found at Knossos, Crete (above and below).

The Bronze Age in Crete began in 2700 BC and ended in 1700 BC; during this time, the Minoan civilisation grew and developed into a thriving, populous society. But, at around 1700 BC, there was some kind of cataclysm, either an invasion by Anatolians or an earthquake. The palaces were destroyed and the population decimated, but, quickly enough, the Minoans rebuilt their palaces and the population re-spawned.

This time around, the palaces were built larger and settlements sprang up all across the island of Crete, marking the apex of Minoan culture.

Around 100 years after the initial disturbance, another catastrophe hit, possibly an eruption of the Thera volcano. The Minoans rebuilt again but their style had changed drastically.

Crete had influenced (and continued to influence) the societies of Egypt and the rest of Greece, and in turn, they were themselves influenced by the world at large. The Cretan fleets were well organised, they were the island’s protectors and the tendrils with which influence could be spread and amassed.

At around 1450 BC, the Minoans faced their next huge and devastating natural event — either an earthquake or volcano. This final shot seems to have signaled the Minoan’s demise. Their palaces were once again in ruins, but this time, they were not rebuilt.

The Myceneans — the first people to speak Greek (1650 to 1200 BC) — took this opportunity to take over the island of Crete. The Mycenaean take-over seems to have been virtually complete. They adapted the Minoan language (Linear A language – see below) to suit their own needs. They even continued to use Minoan cultural practices and political and economic systems. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, I guess.

The downfall of the Minoans was quick and almost total. It is not known exactly how such a powerful and advanced civilisation could have fallen so far from grace. Within the space of a few hundred years, their entire society was in ruins, and less advanced foreign visitors appeared at the reigns.

Some historians believe that an earthquake or volcano wiped out much of the island’s buildings and inhabitants. This was then followed by a tsunami which destroyed their military fleet. The Minoans relied heavily upon their fleet for defence and once that had been dashed against the rocks, marauding invaders from elsewhere could simply walk through the front door.

Others believe that Crete’s “lost” civilisation could be the birth of the Atlantis myth: an advanced and relatively peaceful society which all but disappeared into the sea.

This is the famous “dolphin frieze” at the palace of Knossos:

As for the Minoan art that they left behind, below are some images from the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, near Knossos. The samples are amazing, not just because of the sheer number, but because of their faintly modern tinge, and even more so, the sense of fun which seems to be imbued in them.

The pottery is beautifully decorated and speaks of an island nation, at one with the sea and without so much as a nod towards war (apart from the axes of course, although they are supposed to be ceremonial). Interestingly, if the art of the Minoans is to be believed, the women were considered equals in Minoan society and, even more interestingly, the fashion of the day appears to have been “breasts out:”

(Click to enlarge)

Minoan Language: Linear A and B

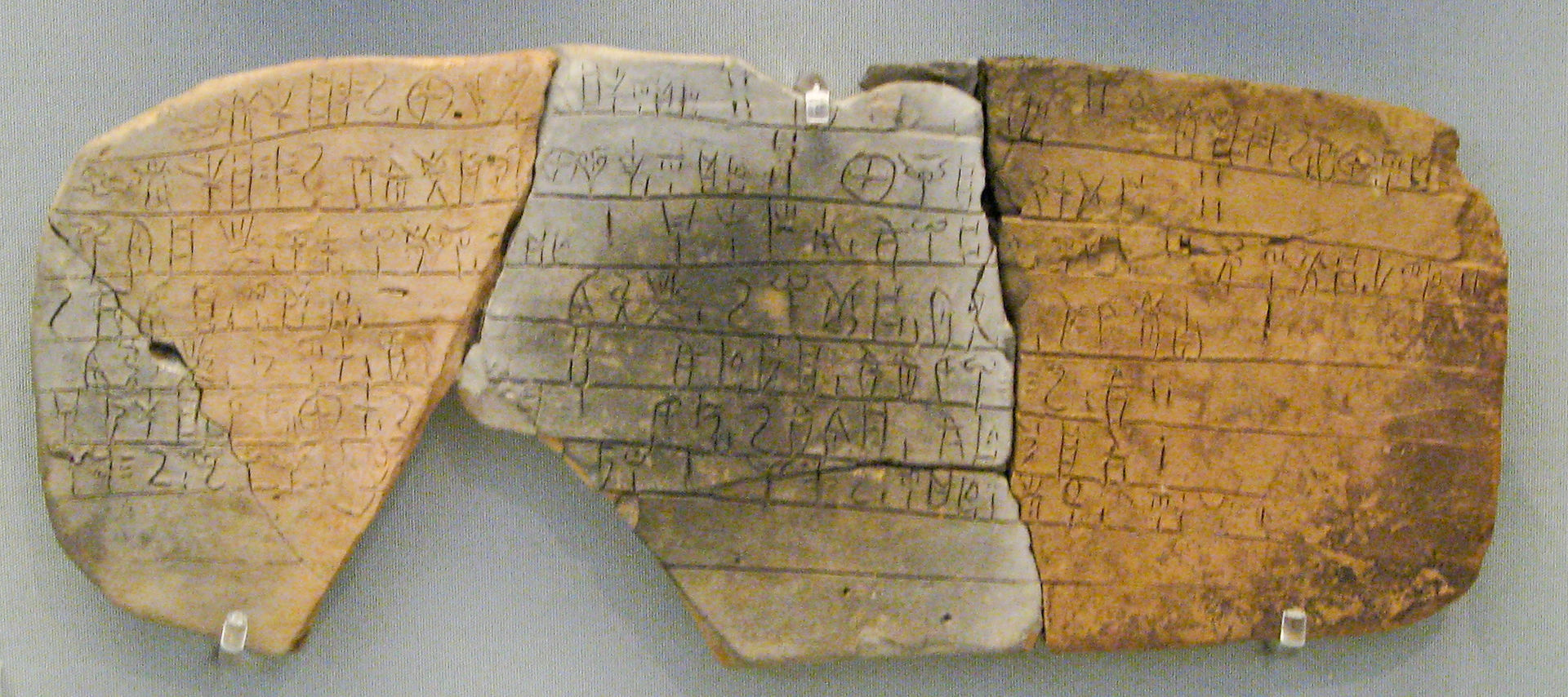

There is little evidence left of the Minoan language. What we do have has been left on clay tablets, some dating back further than 3000 BC.

The original Minoan language has been called Linear A and the later, Mycenaean influenced language – Linear B. Linear B (below) is considered a very early version of Greek although it predates it by several centuries.

Linear A consists of hundreds of symbols and so far has defied translation. Linear B, however, has been successfully translated. Much of the scripts we have left behind are of a very practical nature:

The major cities and palaces used Linear B for records of disbursements of goods. Wool, sheep, and grain were some common items, often given to groups of religious people and to groups of “men watching the coastline.”

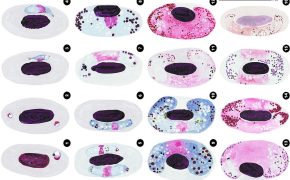

The disc pictured above is the Phaistos disc. To date, no one has managed to crack the code, despite much effort by archaeologists and code breakers. The language is neither Linear A nor B and it steadfastly defies translation. For more infotmation on the efforts to translate the Phaistos disc click HERE.

Although the Minoan civilisation was all but wiped out, their indelible trace was left on the civilisations of North Africa and Greece. Although they don’t get much of a mention anymore, I for one am glad to know a little bit more about our ancient cousins.

MORE FROM THE ANCIENTS:

RONGO RONGO: THE UNBREAKABLE CODE

DID THE AMAZON BASIN HOUSE AN ANCIENT CITY?

THE MAKAPANSGAT PEBBLE – GLIMPSE INTO AN ANCIENT MIND