Barge Haulers On The Volga: The Life Of A Burlak

The painting above is Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870-1873) by Russian artist Ilya Repin. In Russia, it is iconic and has slipped into popular culture; it is at once a memory of harsher times and of national stoic pride. Here we take a brief look at the life of barge haulers beyond the painting.

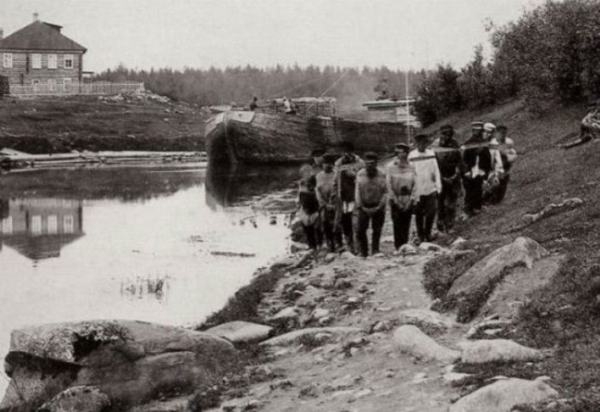

Repin’s depiction of barge haulers shows a group of surly, downtrodden types, working on the banks of the Volga, literally hauling barges. Barge-hauling work was a regular trade from the 16th century (when freight-hauling became popular) all the way into 20th century Soviet Russia.

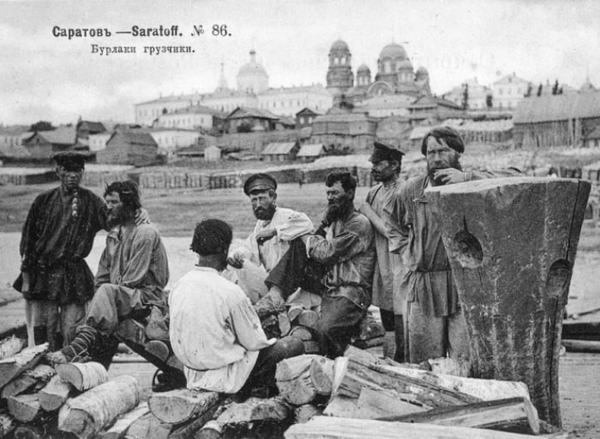

Barge haulers were called burlaks, from a Tatar word meaning “homeless;” so called because they were often homeless, burlaks would often earn their daily bread working on the waterways of Russia. Often, pay was so meager that the men would return home in debt once the season was done.

However, other, non-homeless people who took on this profession did manage to earn enough money to live; in fact, they could earn enough to see them through the off season when boats were prevented from travelling due to ice and bad weather.

Barge-hauling groups ranged in size, sometimes there were just 4 to 6 people, other times 40-60 and, in rare circumstances, 150 men and women would be used in unison.

Although barge haulers were a burly disorganised-looking group of men (and sometimes women), there was some order in the madness. A more experienced, better paid worker would always be up the front; he would set the rhythm, perhaps with the aid of songs (see below) or chanting.

On either side of the leader were “one-siders” who worked for their daily bread. These one-siders were paid in food in advance, so, to make sure they kept up the pace and didn’t idle, they’d have eager, younger boys coming up the rear to whip them into shape.

Repin had been taken by the burlak’s sturdy, stalwart nature as he watched them during a summer holiday. The group structure described above was faithfully reproduced in Repin’s painting. In fact, he carried out some research before painting Barge Haulers on the Volga; he spent a summer in Samara investigating their social structure. Although, after reading the following quote, I’m not sure exactly what he was after. He said:

“I must confess frankly that I wasn’t interested in the question of life and social structure of contracts with the owners of haulers; I asked them, just to seem serious. To tell the truth, I even vaguely listened to some stories or the details of their relationship with the owners.”

The leader of the barge-hauling gang in Repin’s painting was a defrocked priest, called Kanin. Repin was rather struck by him:

“There was something Eastern about it, the face of a Scyth… and what eyes! What depth of vision!… And his brow, so large and wise… He seemed to me a colossal mystery, and for that reason I loved him. Kanin, with a rag around his head, his head in patches made by himself and then worn out, appeared none the less as a man of dignity; he was like a saint.”

Although critically acclaimed today, the painting almost dumped Repin in hot water when it was shown at the World Exhibition in Vienna in 1873. Of course, the barge haulers depicted are not necessarily the squeaky clean, industrious image that Russian leaders wanted to show to a European audience.

Like most countries, especially a proud, struggling country, Russia wanted to keep scruffier people well away from international eyes. As a piece of art, Barge Haulers on the Volga was considered by many top brass to be an uncomfortable break from Romanticism and rather too close to the truth.

Apparently, the Russian Minister of Railways was indignant:

“Well, what [inspired] you to [paint] this ridiculous picture? This antediluvian transport has been reduced to zero by me, and soon there will be no signs of it!”

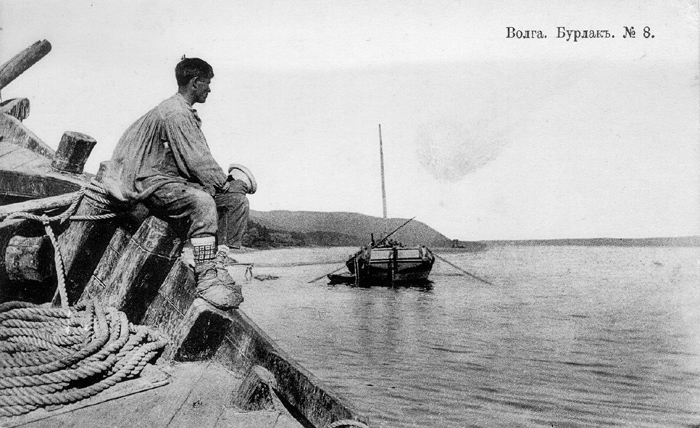

In other words, steam power was on the rise, and the usage of barge haulers had dropped significantly – they were considered old-fashioned and redundant; certainly not something a forward-thinking, progressive super power would need to use.

Russian officials weren’t keen on their country appearing backwards in any way. Thankfully for Repin, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich (son of Emperor Alexander II and brother of Tsar Alexander III) was a fan of his work and eventually bought the painting. His rich patron may have saved his skin.

As for the barge-hauling burlaks, steam power eventually rendered them almost entirely unnecessary. During the first 50 years of 19th century, the number of burlaks working the Volga and Oka rivers dropped from 600,000 to around 150,000. By the beginning of the twentieth century, they had all but disappeared. Some art historians believe that the steamboat chugging in the background of Repin’s painting might be a nod to the fact that it was a dying trade.

For the sake of completeness, below is a recording of a song called The Song of the Volga Boatmen, a tune apparently sung by these hardworking burlaks on the Volga. It was popularised by Feodor Chaliapin and is suitably maudlin:

MORE:

PHOTOS FROM SIBERIA 150 YEARS AGO

RUSSIAN PILGRIMAGE IN THE EARLY 1900S

MORE PAINTINGS FROM ILYA REPIN